Alexey Uvarov explains civil society’s struggle to commemorate repression victims.

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Russia has witnessed competing approaches toward remembering Stalin’s era of mass repression. Often, the discussion around the historical memory of Soviet repression is stereotyped as driven by Muscovite intellectual elites. Yet to understand the broader dynamics of memory-making in Russia, we need to look beyond Moscow. Then, we will see how local communities across Russia have independently driven memorial efforts for decades, highlighting that the impulse to remember repressions’ victims is of much value to ordinary citizens, deeply connected to their personal and local histories.

Since the 1990s, a network of grassroots memorial initiatives has emerged. Ordinary people, local historians, activists, and descendants of repression victims have created monuments, museums, and more across Russia’s regions — often in the face of indifference or even hostility from the state. Their persistence reveals the resilience of civil society under increasingly authoritarian conditions.

As of 2023, around two thousand monuments to the victims of political repression in the USSR have been installed in Russia since 1988. However, this process was not continuous. The majority of these memorials were erected in the 1990s and early 2000s, during a wave of public reckoning with Soviet-era crimes. By 2010, over 1,700 such monuments had been installed, driven largely by grassroots initiatives and countrywide organisations like Memorial.

By the mid-2010s, independent efforts faced increasing restrictions, with authorities blocking (like in Borovsk, Yakutsk and Novgorod) new installations, limiting access to execution sites, and even removing existing memorials. The key exception to this decline was the

Until the mid-2010s, the Kremlin appeared to sanction a form of

In 2017, President Putin inaugurated the

By 2020, however, cracks in the state’s commemorative stance grew apparent. Prosecutors began reexamining Soviet convictions labeled as ‘unjust, ’ particularly those of alleged Nazi collaborators, signaling that the Kremlin might no longer regard all repressions as crimes of the Soviet regime. This reevaluation accelerated dramatically after the full-scale invasion in 2022, when thousands of earlier rehabilitations were revoked in secretive court and prosecutorial proceedings. Official rhetoric increasingly invoked ideas of

Consequently, the conflict between activists, who strive to keep the memory of repressions alive, and the Kremlin, which seeks to rewrite or minimise that painful history, intensified. Many believe the state’s hostility toward these memorials stems from a need to preserve a nostalgic, heroic image of the Soviet Union — admitting the full extent of the terror could undermine its current ideological stance and raise unsettling questions about continuity between past and present repressive methods.

The Kremlin’s

A good example here is the Sandarmokh memorial site in Karelia, a Russian region bordering Finland. The site was discovered in 1997. Thousands of political prisoners from the infamous Solovetsky camps were executed and buried there in secret mass graves during the height of Stalin’s terror. For over twenty years, Sandarmokh drew annual commemorations attended by people from Russia and beyond. Yuri Dmitriev, a historian and researcher of Soviet-era mass executions, played a crucial role in uncovering the burial sites.

Over the years, Dmitriev helped identify the names of more than 6,200 victims resting there, turning the site into a significant memorial cemetery. Reflecting on the challenges of locating execution sites, Dmitriev said:

In 2016, as Russian authorities pushed an alternative narrative about Sandarmokh, Yuri Dmitriev was arrested on charges of child abuse and possession of child pornography. While initially acquitted of the most serious accusations, the verdict was overturned, and he was retried and sentenced to 13 years in prison, later increased to 15 years.

Independent experts found no evidence supporting the Kremlin’s claims. Dimitriev adopted a three-year-old, and since she was sickly from a young age, he photographed her and measured her height and weight for years, keeping all information in a

Recently, however, authorities in Karelia began supporting an alternate interpretation of the site, suggesting the graves contain Soviet soldiers executed by Finnish forces — despite overwhelming historical evidence of Soviet responsibility. In a further crackdown, Sergey Koltyrin, a museum director who studied mass executions at Sandarmokh, was imprisoned on dubious charges in 2019 and died in custody in April 2020.

A similar struggle over historical memory can be seen in efforts to preserve sites of Soviet repression, such as Siberia’s Perm-36 Museum — the only remaining Gulag camp in Russia. Perm-36 is unique among former Gulag sites in Russia because it is the only camp that has been fully preserved as a museum on its original territory. Unlike most other camps — especially those in remote regions like Kolyma — Perm-36 retains its original buildings, including barracks and guard towers. The idea for the museum came to Shmyrov during a 1992 expedition to former political labor camps, organised with activists from the Perm branch of Memorial and accompanied by several former inmates. At the former Perm-36 camp in the village of Kuchino, locals had already dismantled much of the site for building materials. As the group explored the area, villagers observed them closely, recognising some of the former prisoners.

Seeing the site’s historical significance and the risk of its complete erasure, Shmyrov made a simple yet resolute decision:

This unorthodox funding helped kickstart the restoration. By 1995, the special regime barracks, one of the camp’s main buildings, was

However, the museum’s growing influence drew government scrutiny. In 2014, authorities stripped Shmyrov and his team of control, turning Perm-36 into a state-run institution and altering its exhibitions. The removal of its original curators was seen as part of a broader effort to rewrite history. Viktor Shmyrov emphasised that the collection had been assembled independently and with integrity — and that it would not be surrendered to efforts that distort its meaning or historical truth. Despite political pressure, Perm-36 remains a symbol of historical resistance, reminding future generations of the Soviet Union’s repression and the importance of preserving memory.

Civil society’s struggle to protect historical truth from the Kremlin extends throughout Russia. In Yoshkar-Ola, the Gulag History Museum, founded in a former NKVD detention center, was shut down by 2018 under vague pretexts, and its exhibits dismantled. In Yakutia, grassroots memorials thrived in the 1990s but faced gradual government resistance, culminating in the 2023 removal of a monument dedicated to Polish exiles. Even Moscow’s Gulag History Museum was abruptly closed in 2024 under bureaucratic justifications, part of a broader effort to suppress historical truth.

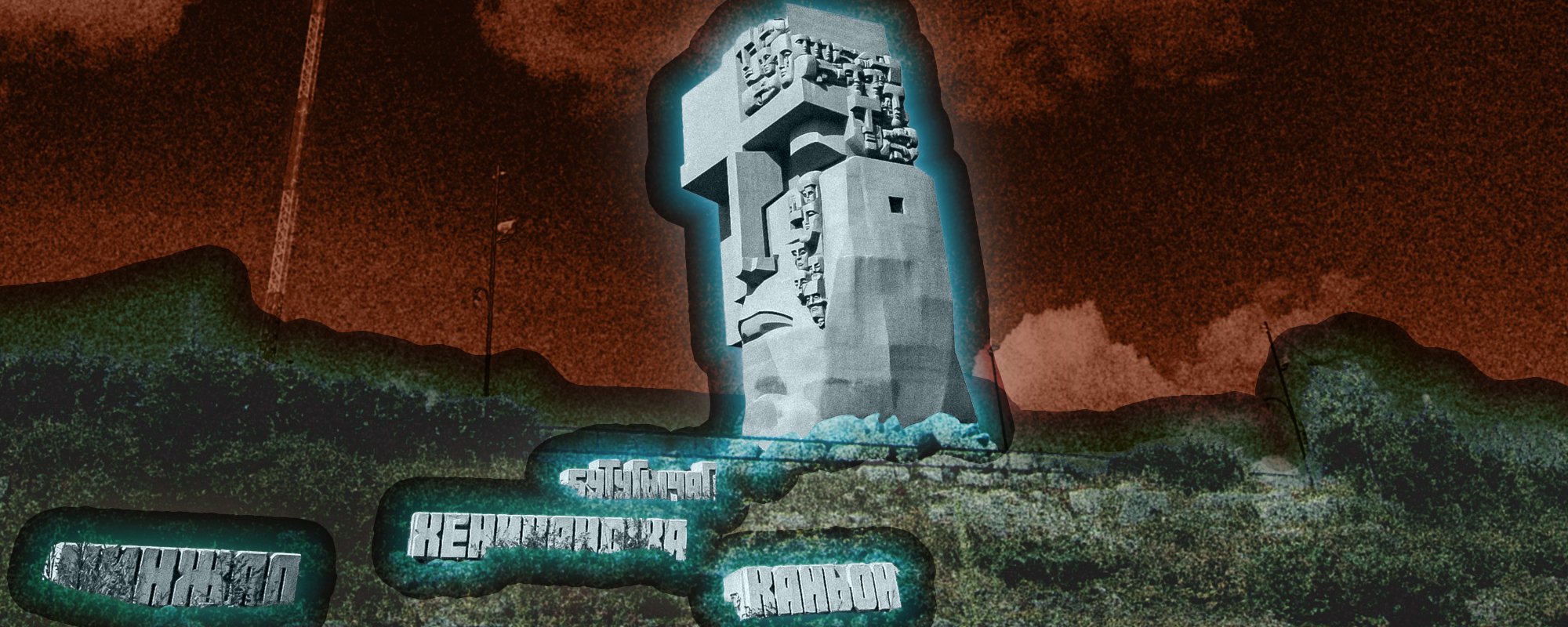

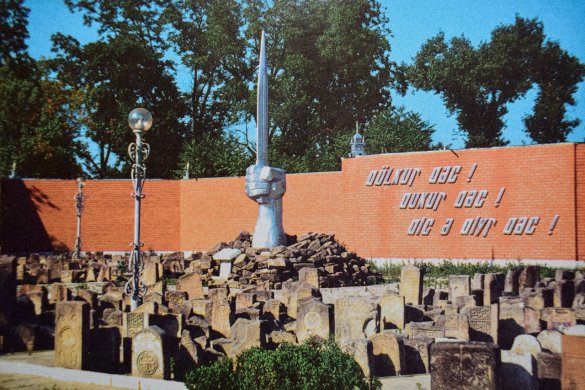

The repression is also evident in the North Caucasus, where the legacy of the 1944 deportations remains a deeply contested issue. Despite official restrictions, remembrance of Stalinist repression endures through grassroots memorials, religious gatherings, and storytelling. However, authorities continue to suppress independent historical initiatives. The Memorial to the Victims of Stalinism in Dagestan and the Memorial to the Victims of Deportation in Grozny, once powerful symbols of remembrance, have faced state interference — the one in Grozny was dismantled and parts of it moved to an entirely new spot in February 2014, the same month the Crimea annexation began. In 2019, the moved gravestones, which made up the memorial, were moved to a new spot once again.

Across Russia, state actions reveal a systematic attempt to control narratives of the Soviet past, erasing uncomfortable histories while local communities continue to resist through informal acts of remembrance. Yet, despite mounting obstacles, local communities persist in their efforts to honor the victims.

From small towns to major cities, dedicated groups continue to hold commemorations, install plaques, conduct independent research, and organise informal gatherings. This ongoing struggle over memory reflects a broader conflict between civil society and state authorities seeking to control historical narratives. Even as public space for discussion shrinks, grassroots remembrance efforts endure, ensuring that the stories of millions who suffered are not erased.

One such effort is the Last Address project, which relies on personal commitment and community involvement to preserve historical memory despite growing hostility from authorities. Initiated in 2014 by journalist Sergey Parkhomenko, it installs small commemorative plaques on buildings, marking the final residences of victims arrested and executed during Stalin’s repressions.

Originally concentrated in major cities like Moscow and Saint Petersburg, the project quickly expanded to smaller towns and even remote villages. As Parkhomenko explains:

The fundamental principle of the initiative is its grassroots funding — each plaque is financed by individual applicants who have personal connections to the commemorated victim.

The project faces mounting hostility since 2022, with many plaques vandalised or removed. Despite authorities rarely investigating such incidents seriously, activists persistently reinstall the plaques, reaffirming Parkhomenko’s determination:

Alexey Uvarov,

a researcher at the University of Bonn. He is a historian specialising in the Soviet Union and the Russian Federation. Uvarov’s research focuses on memory culture and historical politics in Eastern Europe, and nation-building in the post-Soviet space.

Follow his work on X (Twitter) and Facebook.